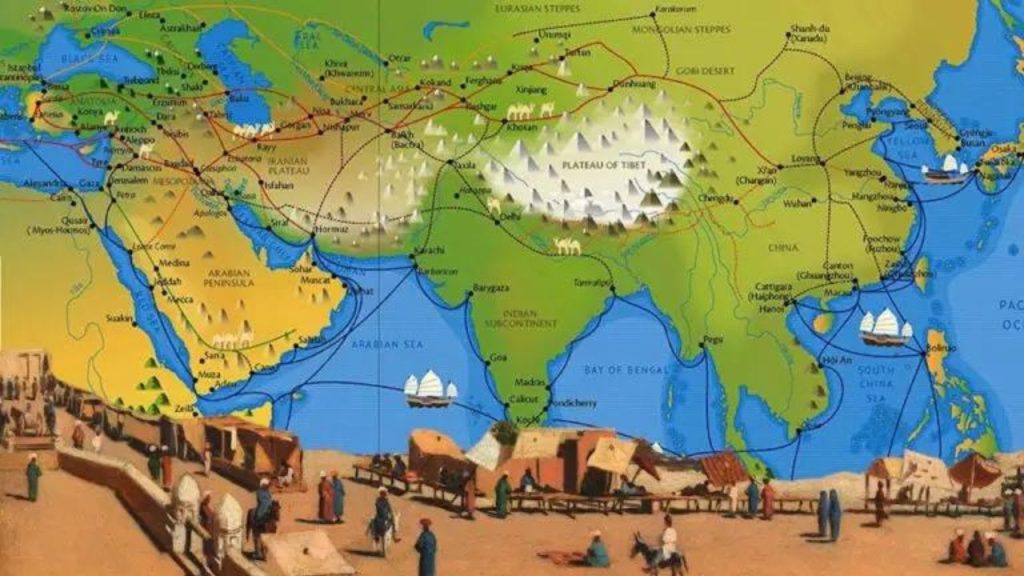

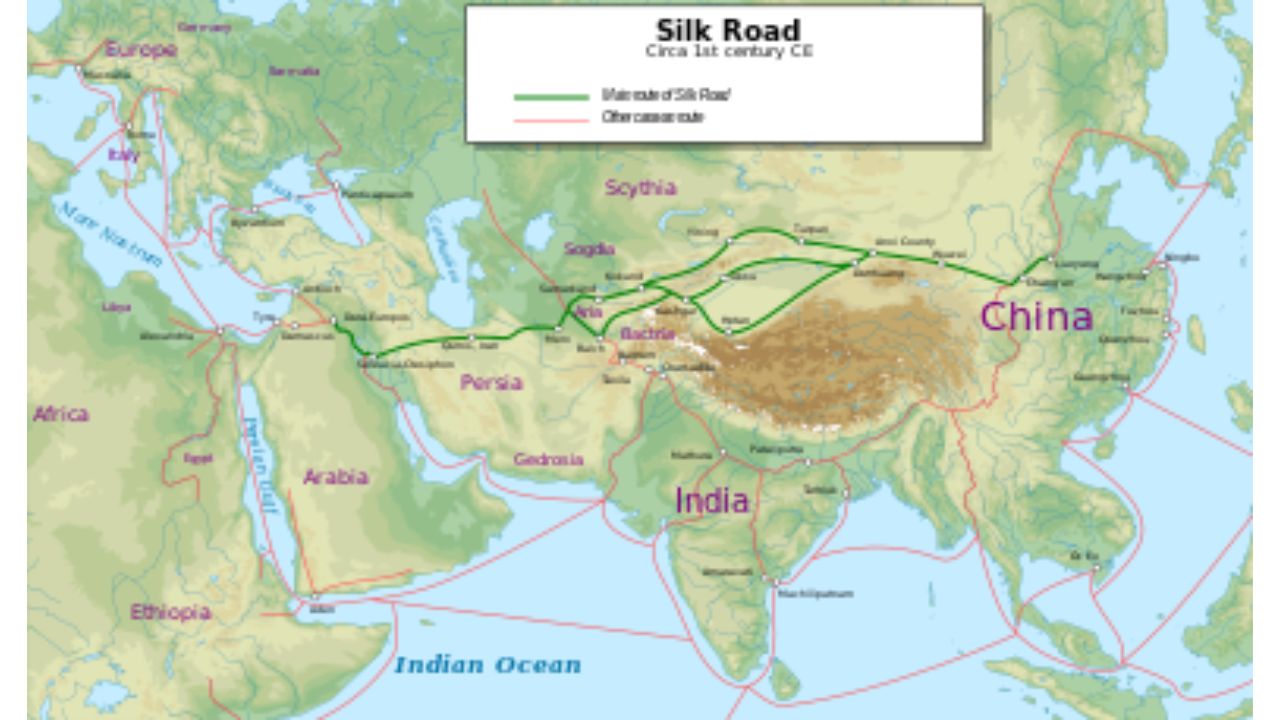

These enormous cities significantly influenced the Silk Road’s cultural, religious, and commercial exchanges. Eastern and Western societies could trade ideas and goods over the Silk Road, which connected Asia and Europe. Many cities sprang up and developed into cross-cultural melting pots along the way.

About Silk Road?

This fabled historic trade route traversed the enormous Central Asian peninsula to connect Asia and Europe. Traders and travellers came from places along the Silk Road, including modern-day China, Iran, Turkey, Greece, and Italy. From 202 BCE to 9 CE, the Western Han Dynasty laid the foundation for the Silk Road. The most international activity on the Silk Road occurred during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE).

There is proof of an almost constant movement of products and ideas throughout Eurasia from archaeological findings and surviving writings, particularly those found in the last 20 years. From East to West, porcelain, silk, paper, and gunpowder were transported, while chariots, wool, glass, and wine entered China. Even rhinoceros and ostriches made their way to Chang’an, the home of the Chinese royal court. The Silk Road was a cultural melting pot due to the connecting of many foreign nations, and this was best demonstrated by the cities that sprung up along the historic trading routes.

Chang’an (Near Xi’an):

The Silk Road is thought to have originated in Shaanxi Province, namely in the ancient city of Chang’an, which is located close to the modern-day metropolis of Xi’an. Chang’an had over a million residents at its most prosperous, making it one of the world’s biggest cities. Being the epicentre of ancient China’s politics, economy, and culture, Chang’an was a well-liked travel destination for outsiders, most of whom arrived along the Silk Road.

Chang’an’s two principal markets during the Tang Dynasty were the West and the East. The Western market was available to the general public. It was well-known for trading foreign commodities, while the eastern market was mainly reserved for nobles and members of the imperial family. The Western market grew into a thriving commercial hub with jewellery, silk, tea, exotic plants, and unusual medicines, among other items worldwide. Through commercial links with other nations along the Silk Road, Chang’an experienced cultural and artistic influences that shaped local tastes in everything from food to dress.

Dunhuang:

For millennia, Dunhuang was a significant Silk Road military, cultural, and commercial hub. Dunhuang is the meeting point of the three Chinese provinces of Xinjiang, Qinghai, and Gansu at the westernmost end of the Hexi Corridor. The Gobi Desert envelops this little oasis. Dunhuang was vital, linking Xinjiang and Central Asia to the west with the Chinese Central Plains to the east.

During the second year of Emperor Wu’s rule (121 BCE), the Han army triumphed against the Xiongnu army. Dunhuang grew in importance as a hub for imperial military, trade, culture, politics, and transportation on the route connecting the Western Regions with the Central Plains. Throughout the arduous voyage, Dunhuang served as a transit hub for the trading of goods as well as a haven for people and animals due to the challenging communication circumstances, sluggish travel, and harsh natural surroundings.

The first location in the East where Buddhism was introduced was Dunhuang. In the Jin Dynasty (266–420 CE), Zhu Fahu and his followers propagated teachings and translated Buddhist texts into Dunhuang. Lezun, a monk, visited Dunhuang shortly after and began excavating the first exquisite Mogao Grottoes. The Diamond Sutra, a Buddhist manuscript from the Tang dynasty, is the oldest dated printed book and was discovered at Dunhuang in 1907.

Kashgar:

For centuries, the centre of the Silk Road was Kashgar, the westernmost city in China. Geographically speaking, Kashgar is China’s “Wild West,” located far to the west and close to the countries’ borders with Pakistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. As the hub for caravans travelling east across the treacherous Taklamakan Desert or westward towards Samarkand, the city flourished as the meeting place between Central Asia and China.

Legend has it that the Han Chinese Emperor Wu discovered that the locals rode unique horses that descended from heaven and shed blood. He dispatched an ambassador because he intended to use these horses in his army. Thanks to this expedition, China now has access to the western regions outside of the desert. Since the Chinese claimed the inhabitants and the oasis of Kashgar, They have governed over Kashgar for fewer than 500 years, with several interruptions throughout the previous two millennia. However, they have never held total authority over the region. The Uyghur minority still comprises most people in the historic oasis city.

Over the last century, Kashgar emerged as the focal point of machinations and scheming, serving as a point of dispute among the three major global empires: China, Russia, and England. They engaged in what was dubbed the “Great Game,” which involved clashing over control of Central Asia and its wealth. Global explorers, adventurers, commanders and archaeologists, spies, and ambassadors joined at Kashgar.

Samarkand:

The transcontinental commerce in luxury commodities, the primary source of China’s prosperity during the Tang dynasty, was mainly organized by the Sogdians, who are virtually extinct now. The Sogdians had a highly developed civilization by the end of the first millennium BCE, with walled towns like Samarkand (called Marakanda by the Greeks) and other great cities. Samarkand profited immensely from being in the centre of the Silk Road, situated on a plateau near the westernmost point of the Alai Mountains. Over its lengthy history, the city—founded around 2,750 years ago—has been subjugated by several well-known and formidable kings. Timur (Tamerlane), Genghis Khan, and Alexander the Great are among them.

The Sogdians governed Asia’s most extensive commercial empire during the sixth and eighth centuries. Apart from intensive language instruction, a condition for their success in the most diverse Asian countries was an open-mindedness about religious topics. While numerous Sogdian communities practised Zoroastrianism, they were also receptive to Buddhism, Christianity, and Manichaeism. Their ability to adjust their company to changing political conditions was another key to their success.

Balkh:

Known as the “Mother of Cities,” the ancient city of Balkh was destroyed in the 1220s by Genghis Khan’s troops. Afghanistan was the epicentre of Asian politics, economy, society, and religion. Numerous nomads, soldiers, settlers, explorers, and missionaries came from all over the region to join the Silk Road, and they all left their imprint. Situated on the banks of the Balkh River, Balkh lies 22 kilometres (13 miles) west of Mazar-i-Sharif, the province capital.

Before he wed the stunning Princess Roxanne, Alexander the Great led an army to battle and assassinate the king of Balkh at this location. Before the Arabs invaded Persia in the early 7th century, the Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang, on the road, found that many Buddhists called Balkh home. This is Zoroaster’s birthplace and possibly last resting place, the philosopher who developed the first monotheistic faith 3,500 years ago. The renowned Persian poet Rumi lived in the 13th century and was born in Balkh. Many Afghans would have it that Rumi was interred here following his passing.

Mary:

The eastern suburbs of Mary, a city in Turkmenistan’s Karakum Desert, are 30 kilometres (18 miles) from the historic town of Merv. Given that it was there for the affluence and glories of the old Silk Road, it is among the most significant historical sites in Turkmenistan and Central Asia. Books written in ancient Persian between the eighth and sixth centuries BCE mention the earliest city of Merv. Merv was a significant Islamic metropolis that rivalled Damascus, Baghdad, and Cairo during its height of growth in the 12th century CE. It had a considerable influence on the Islamic culture of the region.

Throughout history, the historic city of Merv served as a crossroads for several dynasties, serving as a junction between Persia and Central Asia. The metropolis kept growing and showed off various architectural and cultural traits. The oldest remaining building in the ancient city is El Kekara, a citadel constructed in the sixth century BCE by the Persian Achaemenid dynasty and located on its highest point. The town had Buddhist, Zoroastrian, and Christian temples, and the Parthians, Sassanids, and Seljuk Turks all left their imprints.

The historic city of Merv was utterly destroyed in the thirteenth century. When the Mongolians came in 1218, they insisted on receiving tribute for the legendary Genghis Khan. But once the emissary was slain, Tolui, the son of Genghis Khan, led an army into the city in 1221, destroyed it, slaughtered hundreds of thousands of people, and quickly reduced the once-prosperous Merv to ashes.

Ctesiphon:

A magnificent metropolis in prehistoric Mesopotamia, Ctesiphon served as the seat of the Parthian Empire and the Sassanid Dynasty, which succeeded it. It is situated southeast of Iraq’s capital, Baghdad, on the Tigris River’s banks. After being first fortified by Mithridates I of Parthia against the Seleucid dynasty, the Sasanian Empire and the Romans subsequently took over this location. Umar, the second Islamic Caliph, dispatched soldiers to conquer Iraq while he was in charge. After defeating the Sassanid army in 637 CE, the Arab military seized control of the city and used it as a springboard to conquer eastern Persia.

Ctesiphon developed into a significant Silk Road political and commercial hub after hundreds of years of occupancy. At the time, the people thought of Ctesiphon as a utopia on earth, but now all that’s left of the ancient city’s ruins are several towering mud-brick walls and palaces. The Taq Kasra, the enormous vaulted palace belonging to Sassanid King Khosrow I, is their most well-known. This has the world’s highest single-span brick vault, a 100-foot-tall unreinforced brick arch in the main hall.

Palmyra:

Palmyra, an ancient city in central Syria, was well-known along the Silk Road. Near the Euphrates River and the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea, northeast of Damascus, is Palmyra, an oasis on the border of the Syrian desert. It served as a commerce hub linking the Mediterranean and Europe with the Persian Gulf and Asia as early as the first century CE. In return for glass goods, dyes, and pearls, traders sent Chinese silk, ceramics, and plants through Syria.

The “Pearl of the Desert” of Syria is called Palmyra. The destroyed city comprises six square kilometres (2.3 square miles) of strewn columns, towers, walls, tombs, temples, and other structures. Palmyra proliferated throughout the Roman Empire and peaked in the second century CE when it was the most prominent and wealthiest city in the eastern region. Construction workers working in the Syrian desert found a catacomb at the site of an oil pipeline project in 1957. This was the tomb of Zenobia, the most beautiful and aristocratic Asian queen of ancient Syria, who founded the Palmyrene Empire by rebelling against Roman control between 240 and 274 CE. But in 273 CE, Palmyra was devastated by the Romans.

Damascus:

Syria’s capital, Damascus, is a stunning, sophisticated city with a rich 4,500-year history. It’s situated at the base of the magnificent Mount Qasioun. The seven Barada River tributaries flow through the city day and night, giving this well-known West Asian metropolis life and wealth. As early as 115 CE, ancient accounts claim that Chinese silk was brought to Damascus. Through Petra (in modern-day Jordan), Chinese silks and pottery were brought to the Phoenician Kingdom, which was placed on the east coast of the Mediterranean Sea. The way silk was treated and coloured adapted to the demands of the Romans. After that, it was brought to markets in Damascus and Rome.

Constantinople:

Istanbul has a long history, having been the capital of the Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman, and Turkish empires and the Turkish Republic during its formative years. It has traditionally served as the Near East’s political and religious hub. This city, once known as Constantinople, is a significant hub for the fusion of Eastern and Western philosophy and culture since it encompasses the essence of the ideologies, customs, and artistic expressions of all groups in Europe, Asia, and Africa.

The Greeks originally constructed this city in the 7th century BCE. The town was dubbed Constantinople in 330 CE, and Istanbul wasn’t used until the Ottoman Turks took control of it in 1453. Istanbul, after that, rose to prominence as the Turkish Empire’s capital. Despite the Republic of Turkey’s 1923 decision to relocate the capital to Ankara, Istanbul continues to be Turkey’s largest city. Historically, the sole route for commerce ships travelling from Black Sea nations led through Constantinople, which served as a commercial hub. The city, which marked the conclusion of the Silk Road’s Asian leg, was constructed at the meeting point between Asia and Europe.